-

WE ARE SAYING "I LOVE YOU" MORE THAN EVER

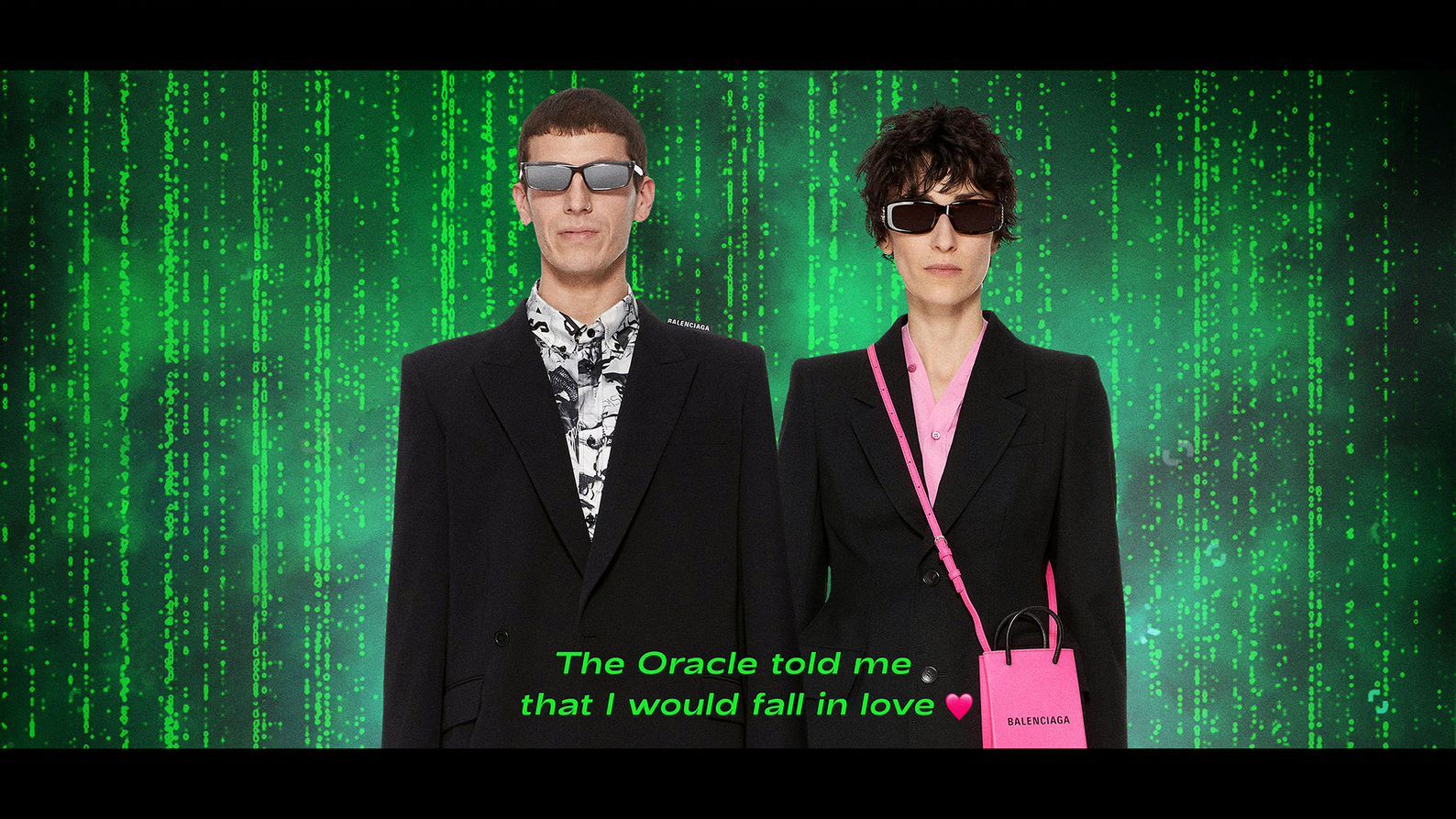

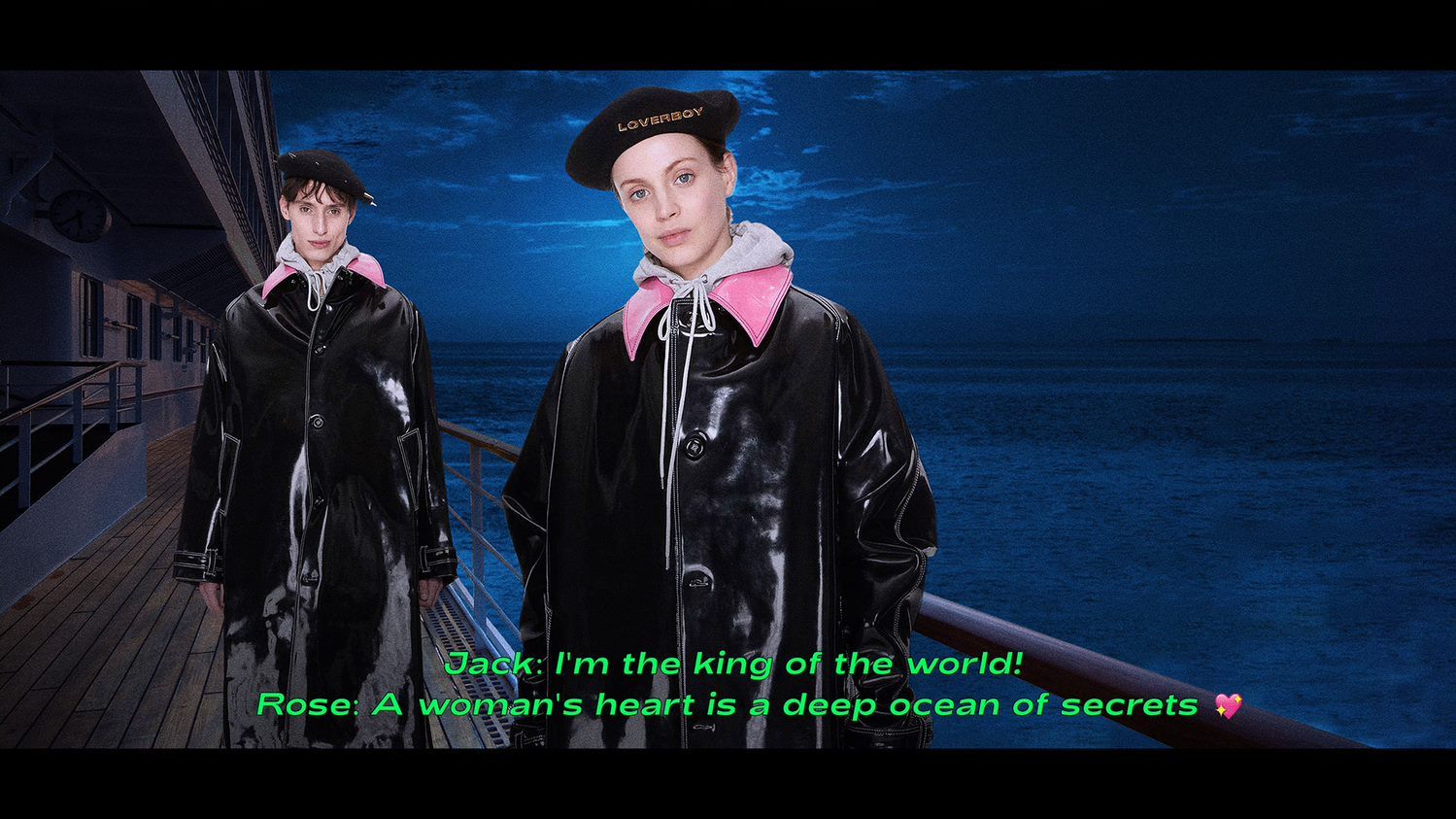

Him. Her.

In the age of selfies and immediacy, what's the easiest way to show your appreciation, sympathy or affection? Thanks to technology, with a single tap under a post, it is now possible to hand out streams of hearts to our loved ones, our friends, our family, and even send them to our favourite brands, distant acquaintances, or celebrities that we'll probably never meet.

Inspired by the organ that pushes blood around the human body, the ancient symbol for love is widely present in our comments and conversations, standardised in the form of emojis that seem to serve as modern-day hieroglyphics. Originally created in the 1980s in Japan, the use of these visual pictograms has only increased, and the heart is still a top favourite. As the Unicode Consortium (the organisation in charge of creating emojis) has revealed, the red heart (❤️) is the second most-used emoji, just behind "face with tears of joy" (😂), and "smiling face with heart eyes" (😍) coming in third. According to the site Emojitracker, that tracks real-time emoji use, no less than 13 billion heart emojis have been sent on Twitter alone since 2013, while the most used hashtag on Instagram is "#love".

So, why so much love? According to Pierre Halté, a doctor in language sciences and professional lecturer at the University of Paris, the emojis that we distil through our messages enhance the degree of subjectivity, by allowing us to evoke an emotion despite the absence of body language. "Communication is not only done with words, but also with gestures and facial expressions. When we move to a digital version, we no longer have our bodies to fulfil these functions, so we seek solutions to fill this gap," he explains.

The "like" button, another example of showing support on social media, is also pervasive. And to symbolise it, the heart is once again gradually overtaking the thumbs up or the star icons. This is particularly the case on Instagram since its creation in 2010, but also on Twitter, which deleted its star icon in 2015 in favour of a red heart. To some extent, the same can be seen on Facebook, which diversified its post reactions since 2016 by adding a heart, laughing, sad and angry emojis alongside the original blue thumbs up. It has been also possible to like direct messages on Instagram, Facebook and the Apple iMessage platform for some time. In short, it looks as though gestures of love have become the be-all and end-all of our online lives.

Changing behaviour

Yet, it is not that simple. Heart emojis and likes do not have the same meaning for everyone, and their use varies depending on the context. Sending the heart-eyes emoji after receiving a photo from your crush does not necessarily have the same meaning as sending one to your boss after they've congratulated you on your latest presentation. Their usage also varies between cultures: Anglo-Saxons are fonder of using love emojis; as it is easier for them to say or write "I love you" to someone, even when it's not someone with whom they are romantically linked. "These geographical differences tend to become blurred with globalisation and the spread of digital tools," adds Halté, author of Les émoticônes et les interjections dans le tchat (Emoticons and Interjections in Chat) in 2018.

But differences in behaviour are apparent between genders. On social networks and in messages, women are more likely to use terms of affection and send heart emojis than their male counterparts. According to an American study from 2016, symbols of joy and appreciation are more common among female users, while funny, sarcastic or awkward emojis, are more often used by men.

Still, the greatest variation in usage is undeniably generational. The younger an internet user is, the more expressive and adoring their emojis are. "When I speak at conferences about this topic, I often meet a grandparent who tells me that their grandchild puts hearts in all their messages, as if it were no big deal, whereas for them it reflects a much stronger sentiment," Halté tells us.

Are we addicted to likes?

Are we witnessing a loss in the meaning of affectionate symbols among the new generation? In Halté's view, "the intensity of the feeling portrayed by the heart depends on the community that is using it." And indeed, this may grow weaker; like the face that's crying with laughter, that we sometimes send compulsively, to only express a slight amusement.

The overuse of love icons is also linked to a desire for recognition and acknowledgement. To encourage us to "like" left, right and centre, Silicon Valley companies had the idea to set up notifications. These activate dopamine in our brains—the same neurotransmitter involved with addictions. The likes that we receive in return for giving out our own are all very quick rewards, reinforcing the appeal for an action that becomes increasingly automatic. Once this vicious circle is in place, one of the more harmful consequences of this addiction to virtual validation is social pressure and comparing ourselves to others. By asking ourselves whether our peers' Instagram account is more successful than ours, we end up envious, and even prone to depression.

Not to mention the fact that on the other side of the screen, web companies are using our likes to display content that we are more likely to enjoy. For influencers, their number of likes has become profitable, enabling them to negotiate sponsorship contracts. Meanwhile, on dating apps such as Tinder, some users have criticised the commodification of human relationships. We swipe right towards the green heart to show that we like the look of someone, as if we're shopping online for clothes. The pitfalls are such that in 2019, Facebook and Instagram set up a panel of users from around the world to test a functionality of hiding the number of likes on another user's post.

But the excessive and sometimes misguided use of love icons is not necessarily the sign of an overall lack of sincerity. The semantic value of the heart remains the same and declarations of love have not disappeared from social media—quite the contrary. On Instagram, the French account @amours_solitaires has almost 800,000 followers and has made over 1,200 posts. Its creator, Morgane Ortin, a former editor who specialises in epistolary writings, publishes screenshots of romantic text messages that users send in to her. These beautiful, raw, funny and poetic messages prove that passion is not dead. Since its creation in 2017, it has been so successful that it was followed by a book as well as a web series broadcasted on Arte's website [a cultural channel].

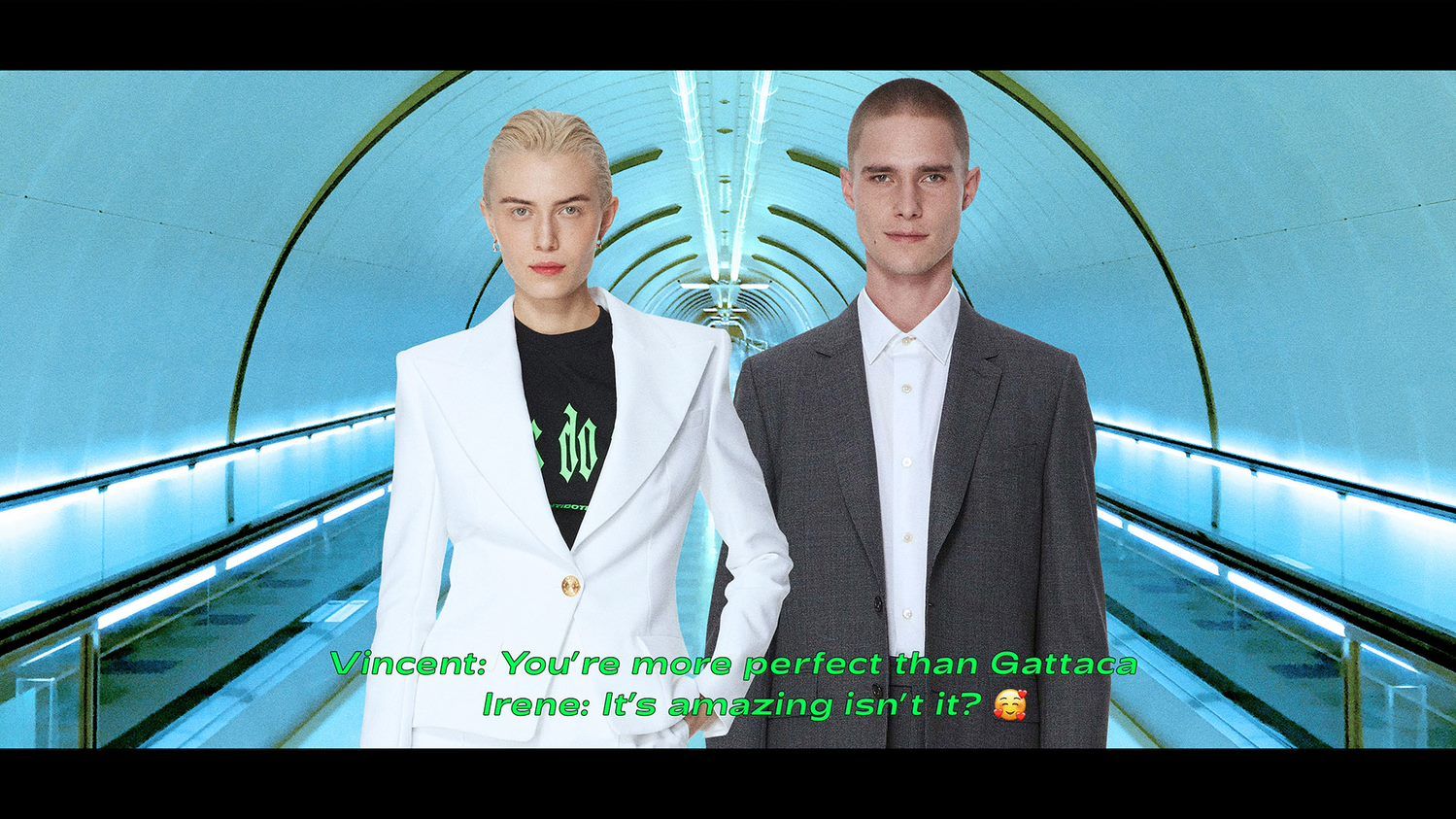

Them.

Does the ❤️ indicate a need for human contact?

For Veikko Eranti, Finnish sociologist and author of a study on the meaning behind Facebook's "like " button, the overrepresentation of the heart is positive. "The fact that the heart is one of the internet's favourite symbols and that digital platforms have chosen it over the star or the thumbs up is not insignificant," he explains. "It means that we want to enhance our conversations with human warmth." For Eranti, the practice of "liking" things also has the advantage of reversing certain toxic masculine norms. "This widespread use of hearts also has the benefit of extending this vocabulary to men, who have a tendency to conceal their emotions. This common language allows some to open up more".

In 2020, the experience of a global lockdown to slow the spread of the Coronavirus probably helped to proliferate this behaviour online. During the height of the pandemic, the use of social media skyrocketed; particularly WhatsApp, seeing an increase by 40% of its usage. To stave off the doom and gloom and continue to say "I love you" despite the distance, families, friends and couples turned to digital devices.

"Lockdown certainly resulted in a much higher use of digital tools and emojis," says Pierre Halté. And despite being confined to long chats online, romantic dates have not been left behind; Tinder recorded a global spike in users during the pandemic. "We have to learn to overcome the human disconnect and show affection in alternative ways," Eranti concludes. Perhaps the best is yet to come for digital expressions of love 💕.